In November, New York City voters overwhelmingly approved ranked-choice voting for future municipal elections. Advocates for electoral systems reform heralded the victory as a watershed moment in the modern pro-democracy movement. However, this interpretation misses a key point: This is actually the second time the Big Apple has turned to ranked-choice voting.

Looking back at the past can bring a new understanding for the future of RCV in NYC. How it gets implemented will be critical to understanding how this reform can truly lift up the voices of communities of color.

The city first adopted RCV in 1936, when the United States was recovering from the throes of the Great Depression and citizens worldwide were facing the rise of totalitarianism. Times were uncertain and reformers looked for representation as a way to ensure the interests of local citizens were met. Their biggest barrier was the "first-past-the-post" electoral system.

Before 1936, and for some time after 1945, the city's use of a first-past-the-post system enabled the Tammany Hall Democrats' domination of elections. Tammany Hall was the dominant political machine of its day. It controlled New York's political system, in the city and the state, often winning 95 percent of the City Council seats with only two-thirds of the vote because of the first-past-the-post system — each voter makes a single choice and the candidate with the most votes wins.

New Yorkers had enough, and decided to use a version of RCV known to political scientists as PR-STV, for proportional representation with the single transferable vote, to change the rules and the outcome of political games. Eight decades ago, there were 23 cities across America that had adopted the system.

New York City assigned a number of city councilors for each borough based on total population. And each political party was assigned a number of seats in proportion to city-wide vote totals.

Voters ranked candidates in order of preference on their ballot. Each candidate who surpassed the "threshold of exclusion" or minimum number of votes to win a seat, based on first place votes would be elected. In a borough with five seats, the threshold is 16.7 percent. This is somewhat similar to how the Iowa caucuses determine candidate viability.

Under the rules single-transferable vote, last place candidates are eliminated one by one until the designated number of winners for seats in that borough have been achieved.

Before, the council had been described as a collection of self-serving, career politicians more interested in themselves and their friends than in the lives of New Yorkers. The individuals elected under PR-STV, on the other hand, advocated for enhanced social welfare policies.

The system's adoption instantly helped increase representation for the city's minorities and women. In 1941, Adam Clayton Powell Jr. was elected as the city's first African-American councilmember. (Later he became the city's first African-American representative in Congress.) Similarly, Cincinnati, Hamilton and Toledo also elected their first African-American city council members under a similar system. And this was at a time when Jim Crow's ugly face ruled much of the country, two decades before the civil rights movement flourished.

PR-STV also allowed Genevieve Beavers Earle to become the first woman elected to the New York City Council.

The reform also resulted in the election of candidates from third parties including the American Labor Party and the Communist Party. While they didn't elect enough members to control the council, they were able to influence decisions.

One thing this voting system didn't produce was an increase in voter participation. Some proponents incorrectly hypothesized it would increase the number of voters. However, an analysis of the returns doesn't seem to show a significant increase. Additionally, the data suggests the driving force in turnout was often the popularity, and urgency, of local issues.

Despite increasing representation, New York repealed PR-STV in 1945. Why? Because it worked too well.

Racism and xenophobia were major forces that led to the repeal. The system increased the number of minorities, women and third parties in political office, disrupting the status quo and causing political backlash. Similarly growing anti-immigrant sentiment against Hungarian and Greek candidates winning seats led to repeals in Massachusetts.

Most such repeals, including by New York City, happened on the cusp of the "red scare" and the civil rights movement. Opponents parroted racist talking points about the dangers of increasing African-American representation on legislative bodies and executive offices. Opponents also talked about "communist infiltration" in American democratic systems and scared voters into repealing this form of RCV.

Additionally, the Republican and Democratic parties joined forces in New York in opposition. The GOP did so in part because the American Labor Party garnered five spots on the City Council, which was two more seats than the Republican Party.

While the Democratic machine still held onto a significant portion of the seats, their overall political influence waned because of an increase in third parties and an increase in the number of independent Democrats on the council.

Author Peter Emerson wrote the quality of American democracy must be measured by diversity in representation, as well as by diversity in voting rights. The first-past-the-post system erodes the quality of both.

The status quo is especially bad for communities of color. Segregation of the population is alive and well in the parts of urban America with "majority minority" districts. For people of color to be adequately represented under a first-past-the-post system, in other words, they have to live in segregated neighborhoods.

Additionally, this also means that in jurisdictions without such severe racial segregation, there's often no path for communities of color to fight for voting rights at all.

Between the height of the Depression and the end of World War II, New Yorkers reshaped democracy in the nation's largest city in a time of massive political, social and economic turmoil. They tried to embrace the future of American democracy by enhancing representation of a diverse city in body and mind. Enhancing representation was mostly a novel idea at that time and it's one that's showing up again in the Big Apple and elsewhere.

Put simply, New Yorkers are going back to the future in 2020 with their move to modern-day ranked-choice voting.

Ochoa is communications director of More Equitable Democracy, which advocates for an array of democracy reforms. Cheung is the group's head.

In November, New York City voters overwhelmingly approved ranked-choice voting for future municipal elections. Advocates for electoral systems reform heralded the victory as a watershed moment in the modern pro-democracy movement. However, this interpretation misses a key point: This is actually the second time the Big Apple has turned to ranked-choice voting.

Looking back at the past can bring a new understanding for the future of RCV in NYC. How it gets implemented will be critical to understanding how this reform can truly lift up the voices of communities of color.

The city first adopted RCV in 1936, when the United States was recovering from the throes of the Great Depression and citizens worldwide were facing the rise of totalitarianism. Times were uncertain and reformers looked for representation as a way to ensure the interests of local citizens were met. Their biggest barrier was the "first-past-the-post" electoral system.

Before 1936, and for some time after 1945, the city's use of a first-past-the-post system enabled the Tammany Hall Democrats' domination of elections. Tammany Hall was the dominant political machine of its day. It controlled New York's political system, in the city and the state, often winning 95 percent of the City Council seats with only two-thirds of the vote because of the first-past-the-post system — each voter makes a single choice and the candidate with the most votes wins.

New Yorkers had enough, and decided to use a version of RCV known to political scientists as PR-STV, for proportional representation with the single transferable vote, to change the rules and the outcome of political games. Eight decades ago, there were 23 cities across America that had adopted the system.

New York City assigned a number of city councilors for each borough based on total population. And each political party was assigned a number of seats in proportion to city-wide vote totals.

Voters ranked candidates in order of preference on their ballot. Each candidate who surpassed the "threshold of exclusion" or minimum number of votes to win a seat, based on first place votes would be elected. In a borough with five seats, the threshold is 16.7 percent. This is somewhat similar to how the Iowa caucuses determine candidate viability.

Under the rules single-transferable vote, last place candidates are eliminated one by one until the designated number of winners for seats in that borough have been achieved.

Before, the council had been described as a collection of self-serving, career politicians more interested in themselves and their friends than in the lives of New Yorkers. The individuals elected under PR-STV, on the other hand, advocated for enhanced social welfare policies.

The system's adoption instantly helped increase representation for the city's minorities and women. In 1941, Adam Clayton Powell Jr. was elected as the city's first African-American councilmember. (Later he became the city's first African-American representative in Congress.) Similarly, Cincinnati, Hamilton and Toledo also elected their first African-American city council members under a similar system. And this was at a time when Jim Crow's ugly face ruled much of the country, two decades before the civil rights movement flourished.

PR-STV also allowed Genevieve Beavers Earle to become the first woman elected to the New York City Council.

The reform also resulted in the election of candidates from third parties including the American Labor Party and the Communist Party. While they didn't elect enough members to control the council, they were able to influence decisions.

One thing this voting system didn't produce was an increase in voter participation. Some proponents incorrectly hypothesized it would increase the number of voters. However, an analysis of the returns doesn't seem to show a significant increase. Additionally, the data suggests the driving force in turnout was often the popularity, and urgency, of local issues.

Despite increasing representation, New York repealed PR-STV in 1945. Why? Because it worked too well.

Racism and xenophobia were major forces that led to the repeal. The system increased the number of minorities, women and third parties in political office, disrupting the status quo and causing political backlash. Similarly growing anti-immigrant sentiment against Hungarian and Greek candidates winning seats led to repeals in Massachusetts.

Most such repeals, including by New York City, happened on the cusp of the "red scare" and the civil rights movement. Opponents parroted racist talking points about the dangers of increasing African-American representation on legislative bodies and executive offices. Opponents also talked about "communist infiltration" in American democratic systems and scared voters into repealing this form of RCV.

Additionally, the Republican and Democratic parties joined forces in New York in opposition. The GOP did so in part because the American Labor Party garnered five spots on the City Council, which was two more seats than the Republican Party.

While the Democratic machine still held onto a significant portion of the seats, their overall political influence waned because of an increase in third parties and an increase in the number of independent Democrats on the council.

Author Peter Emerson wrote the quality of American democracy must be measured by diversity in representation, as well as by diversity in voting rights. The first-past-the-post system erodes the quality of both.

The status quo is especially bad for communities of color. Segregation of the population is alive and well in the parts of urban America with "majority minority" districts. For people of color to be adequately represented under a first-past-the-post system, in other words, they have to live in segregated neighborhoods.

Additionally, this also means that in jurisdictions without such severe racial segregation, there's often no path for communities of color to fight for voting rights at all.

Between the height of the Depression and the end of World War II, New Yorkers reshaped democracy in the nation's largest city in a time of massive political, social and economic turmoil. They tried to embrace the future of American democracy by enhancing representation of a diverse city in body and mind. Enhancing representation was mostly a novel idea at that time and it's one that's showing up again in the Big Apple and elsewhere.

Put simply, New Yorkers are going back to the future in 2020 with their move to modern-day ranked-choice voting.

From Your Site Articles

Jessie Harris (left,) a registered independent, casts a ballot at during South Carolina's Republican primary on Feb. 24.

With the race to Election Day entering the homestretch, the Harris and Trump campaigns are in a full out sprint to reach independent voters, knowing full well that independents have been the deciding vote in every presidential contest since the Obama era. And like clockwork every election season, debates are arising about who independent voters are, whether they matter and even whether they actually exist at all.

Lost, perhaps intentionally, in these debates is one undebatable truth: Our electoral system treats the millions of Americans registered as independent voters as second-class citizens by law.

That’s perhaps most well known in our system of primary elections. In 30 states, the government registers voters by party affiliation. The purpose of which is not to ensure election integrity, but to ensure that the government itself can properly segregate voters and advantage some over others. Fifteen states and the District of Columbia bar registered independent voters from participating in primary elections, while 25 more restrict primary voting in certain elections like presidential contests.

Just this year, 27 million Americans who registered as independent were shut out of the presidential primaries. And despite the tired argument that primaries are private affairs, it’s the government that pays for and runs these elections and it’s the government that enforces the Democratic and Republican parties’ desire to shut independent voters out.

That’s hardly the extent to which independent voters are discriminated against by law. Want to support a candidate? Most states bar independent voters not only from signing party candidate petitions for the ballot but even from serving as witnesses to those signatures. These are not internal party rules but state election law, enforced by state-administered election boards.

Want to work to ensure our elections are safe and fair? Open Primaries’ review of state election laws found that a majority of states bar independent voters from serving as poll workers, poll watchers, election judges and even serving on election boards. America’s entire system of election administration shuts out independent voters.

Additional prohibitions are too numerous to list. Arizona, for example, automatically mails ballots to party voters but requires independent voters to preemptively request a ballot. States without party registration are not spared. Tennessee law now requires polling locations to display signage threatening independents with criminal prosecution if they vote in primaries, even though they have open primaries!

The effect is becoming too large to ignore. Recent Gallup polling found that 51 percent of Americans identify as independent, more than Democrats and Republicans combined. That number is an important symbol of just how many Americans are feeling disaffected from the two major parties. But it also helps obscure the equally large number of Americans who are registering as independent and being subjected to government-administered discrimination as a result. Independents are now the largest group of registered voters in 10 states, including Arizona, Colorado, Nevada and North Carolina. And as our country divides into a sea of red and blue states, it’s independent voters who outnumber one of the two major parties voters as the second largest group of voters in almost every other state.

The irony, of course, is that many of the largest constituencies of independent voters are the same constituencies that the Republican and Democratic parties alike claim to champion. More than half (52 percent) of Latinos are independent. So are nearly half of our military veterans. And today over half of millennials and Gen Z voters, having long surpassed baby boomers as the largest group of voters by age, are independent voters.

Just join a party, some say. Imagine the outrage if Republican voters were asked to register as Democrats or vice versa. No American should be forced by their government into a political affiliation whose values they don't share. And no democratic government has the right to ask their citizens to forfeit their rights for refusing such a false choice.

Independent voters are now the fastest growing group of voters in America today. Everyone seems to have an opinion about what that means for the 2024 election. But what it means to millions of independent Americans is simple: You’re a second-class citizen.

Keep Reading Show less

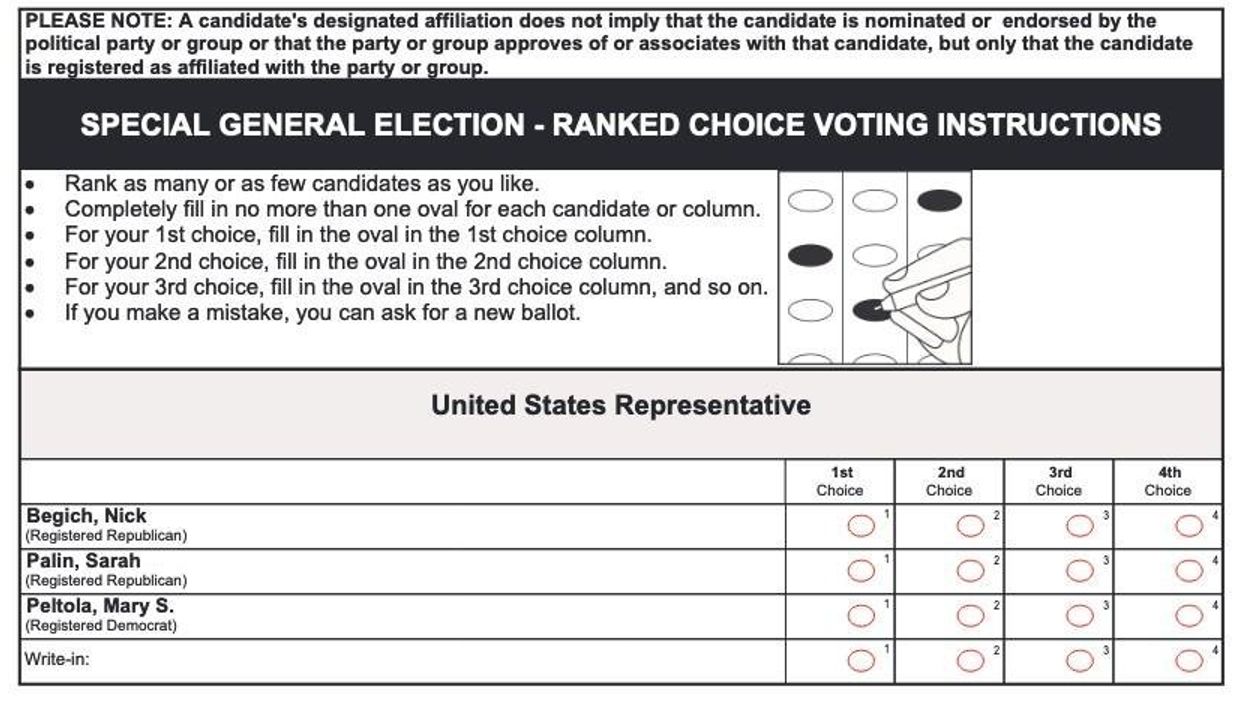

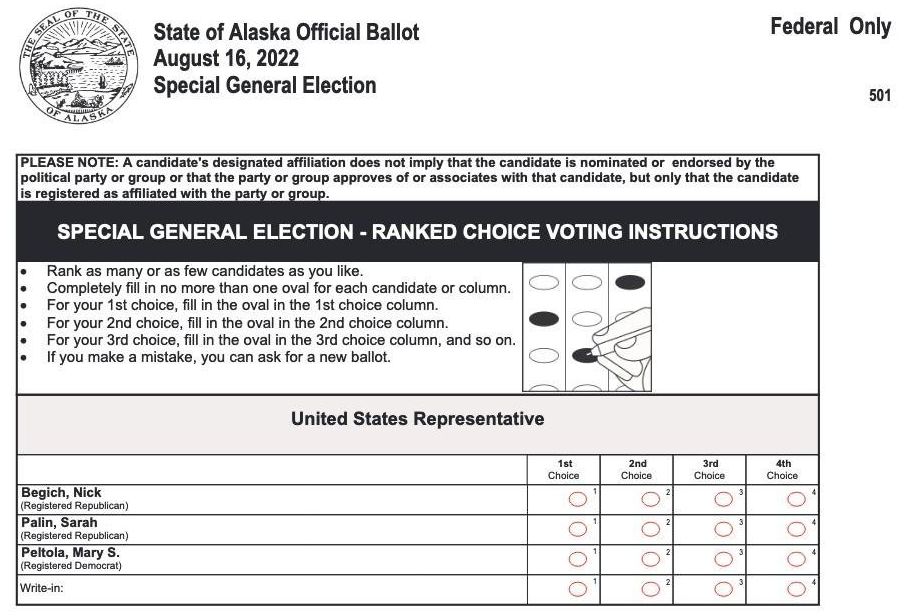

The ballot used in Alaska's 2022 special election.

Landry is the facilitator of the League of Women Voters of Colorado’s Alternative Voting Methods Task Force. An earlier version of this article was published in the LWV of Boulder County’s June 2023 Voter newsletter.

The term “ranked-choice voting” is so bandied about these days that it tends to take up all the oxygen in any discussion on better voting methods. The RCV label was created in 2002 by the city of San Francisco. People who want to promote evolution beyond our flawed plurality voting are often excited to jump on the RCV bandwagon.

However, many people, including RCV advocates, are unaware that it is actually an umbrella term, and ranked-choice voting in fact exists in multiple forms. Some people refer to any alternative voting method as RCV — even approval voting and STAR Voting, which don’t rank candidates! This article only discusses voting methods that do rank candidates.

If you are in the market for a new house or car, you don’t usually buy the first house you visit or the first car you test drive; rather, you shop around. Similarly, the League of Women Voters of Colorado would like activists to consider different voting methods before advocating for a particular method in a particular situation.

Plurality voting is the simplest and most familiar of voting methods. Also known as “first past the post” voting, it works well if a ballot lists only two candidates for a given position.

If our goal is better representative democracy, however, we should strive to adopt voting methods that allow voters to express their preferences more effectively, that encourage more candidates to run and that reduce the so-called spoiler effect, by which a less-popular candidate wins when the spoiler candidate draws sufficient votes away from a popular but similar candidate.

A voting method has at least two components:

In a December 2022 Fair Vote Canada video, professor Dennis Pilon named a third component: district magnitude, or the number of seats to be filled in a ballot contest. We take this component into account by distinguishing between single-winner and multi-winner contests.

Ballot formats for a variety of ranked-voting methods contain the same basic directions: “Rank candidates in order of preference.” In practice, the directions amount to “Fill in at most one bubble per column and one bubble per row.” Voters should always fill in at least a first choice. Below is the ranked ballot that was used in the August 2022 Alaska special election.

The tabulation method is what differentiates the various ranked-voting methods.

First, consider what is unique to RCV tabulation methods, i.e., what defines RCV: All forms of RCV allow for rounds of counting in which the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated and votes for that candidate are transferred to the next-highest-ranked candidate on the ballot.

Within this RCV constraint, tabulation methods can differ widely. The table below lists seven different RCV tabulation methods. (Note that yet another method called RCV in a New Hampshire bill would have allowed voters to give the same ranking, such as the top spot, to multiple candidates, but it did not pass in the 2018 legislative session.)

Unfortunately, the media and activists often conflate single-winner and multi-winner versions of RCV — claiming, for instance, that RCV leads to proportional representation when that statement is true for only some of the multi-winner forms of RCV.

Forms of RCV

Key: SW= single winner, MW = multiple winners

Voting Method

SW or MW?

How It Works

Where It’s Used

Some jurisdictions currently or planning to use this form of RCV

Instant-Runoff Voting (IRV) - What most people think of as “RCV”

video [Video correction: Only a 1st-round winner is guaranteed a majority of all votes]

If no candidate gets a majority of votes in the first round of counting, then the lowest vote-getters are eliminated round-by-round and their votes transferred to the next available ranking on the ballot until 1 candidate has more votes than the remaining candidates combined.

San Francisco, Santa Fe, Maine, New York City and more than a dozen other places;

Boulder in 2023 for its first mayoral election

Top-4 Plurality primary with an IRV general election, similar to Final-Five Voting

All candidates run against each other in a Plurality “choose-one” primary election. The top 4 candidates proceed to an IRV general election. Unlike regular IRV, this version does not eliminate a second election.

Alaska since August 2022

Contingent Vote

(3 or more rankings) or Supplementary Vote (only 2 rankings)

All but the top 2 vote-getters are eliminated in the first round of counting. Votes for eliminated candidates are transferred to the highest ranked of the 2 remaining candidates on each ballot.

NC Court of Appeals 2010; London, UK;

Overseas voters in AR, AL, GA, LA, MS and SC mark a regular primary ballot and a ranked ballot that counts if there is a top-2 runoff

Single Transferable Vote (STV),

aka Proportional RCV (pRCV)

video

[ a “gold standard” proportional voting method to elect people]

Candidates who receive the threshold of votes are elected. Any surplus votes are transferred to the next highest available ranking. Lowest vote-getters are eliminated round-by-round and their votes transferred to the next available ranking on each ballot until all seats are filled.

Cambridge, MA since 1941; Albany, CA as of 2022;

some members of two boards in Minneapolis;

Portland, OR starting in 2024;

Boulder, CO 1917-1947;

Ireland lower house

Bottoms-Up 15% Threshold RCV

[ determine proportional allocations]

Conduct IRV tabulation rounds but don’t stop until all remaining candidates have at least 15% support, whereupon candidates’ delegates are proportionally allocated.

2020 Alaska, Hawaii, Kansas and Wyoming Democratic presidential primaries to allocate delegates to the national nominating convention

Bottoms-Up Top-2 RCV primary with a “choose-one” general election

Conduct IRV tabulation rounds until 2 candidates remain. Voters vote again in a runoff election to decide which of the 2 primary winners gets the seat.

Seattle starting in 2027

Preferential Block Voting (PBV),

aka Sequential RCV

video

[ NOT proportional; a plurality of voters may elect all the winners]

The first seat is filled using an IRV tabulation. Then all ballots are tabulated again using IRV but ignoring the winning candidate. The process is repeated until all seats are filled. (In the video some voters help elect 3 candidates, while voters who ranked Yellow #1 don’t help elect any.)

Utah municipalities may opt into an IRV and PBV pilot project through the 2025 elections.

In 2022 Portland, ME voters approved changing from PBV to proportional STV.

Now we’ll consider some non-RCV ranked-voting methods. The first four methods listed have all mistakenly been called RCV in Colorado in the past few years!

Forms of Non-RCV Ranked Voting

(includes only single-winner voting methods)

Voting Method

How It Works

Where It’s Used

Insurance Ranking

[The ballot’s vote is solely dependent on candidate eligibility, not on the tabulation process.]

If the ballot’s 1st-choice candidate dies, withdraws or is disqualified after the voter has returned their ballot but before Election Day, the vote counts for the next ranking.

2023 Colorado Senate Bill 301 would have allowed military and overseas voters to use this for the 2024 presidential primary election (but the bill died in committee).

Borda Count

Assigns the largest point value to a voter’s 1st choice, 2nd largest to the voter’s 2nd choice, and so on. The candidate with the largest point total wins.

In some overseas political elections and in various organizations and institutions – see Survey Monkey’s Ranking ballot

Bucklin Voting,

aka Grand Junction System

If no candidate gets a majority of 1st-choice rankings, then 2nd-choice rankings are added to the total. If still no candidate gets a majority, then 3rd-choice rankings are added in.

In more than 60 US cities in the early 20th century, including Denver, Grand Junction, Colorado Springs, San Francisco, Cleveland, Newark, and St Petersburg

Count the Rankings

[ arguably more a presentation of raw data than a tabulation method]

Voters must rank all candidates. Count and report the number of 1stchoices, the number of 2ndchoices, and so on for each candidate.

In organizations using Microsoft 365’s Ranking form

Condorcet Method

[actually, a family of voting methods, including Ranked Robin, Minimax, and Schulze>

The candidate that defeats all the opponents in pairwise matchups is the Condorcet winner. If no Condorcet winner exists, each method has a rule to determine a winner.

Mostly by organizations and political parties overseas, as well as high-tech organizations, such as IEEE. A few overseas municipalities use Schulze.

Coombs’ Rule

[ The video contrasts IRV and Coombs’ Rule.]

If no candidate gets a majority on the 1st round, then the candidate with the most last-place votes is eliminated. The process is repeated until one candidate wins.

A variant is used on the “Survivor” reality TV program

So, how do you now approach conversations about voting methods? To cover all bases, consider following the example of the Colorado secretary of state and Colorado statutes: don’t use the term “RCV,” but rather the super-umbrella term “ranked voting.” And, if someone mentions RCV or ranked voting, here’s a good first question to ensure that everyone is on the same page: “Which form of RCV or ranked voting are you talking about?”

Who knew there were so many forms of ranked voting? Well, now you know.

Keep Reading Show less

The New Hampshire Together citizens assembly met in June.

New Hampshire TogetherThe recent work of the New Hampshire Together citizens assembly offers a model for how we can restore faith in our democratic institutions and improve civic engagement through nonpartisan deliberation and actionable reforms.

The citizens assembly, which convened in Manchester in June, brought together 50 New Hampshire residents representing a cross-section of the state’s demographics and political ideologies. Their goal was ambitious: to explore ways to rebuild trust in elections, reduce partisan polarization and increase the responsiveness of the political system to the will of the people.

Over three days of discussion and debate, the participants achieved something that has become increasingly rare in today’s political landscape — they found common ground. By the end of the event, supermajorities supported four key recommendations.

The proposal to emerge from the assembly with the highest level of support (89 percent) was the creation of an independent redistricting commission. By ensuring that district lines are drawn by a nonpartisan body rather than political incumbents, New Hampshire could take a significant step toward restoring fairness in its elections. The commission would work to ensure these districts would be compact, avoiding irregular shapes and keeping communities intact.

The second recommendation focuses on improving voter education, supported by 87 percent of the assembly participants. The proposal calls for creating a nonpartisan working group to collaborate with the New Hampshire secretary of state's office to increase voter awareness about election laws, policies and procedures.

This includes better publicizing election integrity measures, enhancing town websites, disseminating educational materials and making election data (e.g., audits and voter registration statistics) easily accessible. The goal is to foster transparency and trust in the electoral process.

A recommendation that garnered 85 percent support was the introduction of a “single ballot” primary. In this system, all properly registered candidates would be listed on one ballot, with the option for candidates to include their party affiliation if they choose. This reform is intended to open up the primary process, making it more inclusive by eliminating the requirement for voters to declare a party affiliation in order to participate.

This new system would be accompanied by a comprehensive voter education campaign.

The final recommendation was to establish a Civics Education Advisory Board to improve civics education for students from pre-kindergarten through 12th grade. The 83 percent support for this recommendation highlights the broad recognition that reinvigorating civics education is essential for fostering engaged and informed future voters.

A comprehensive civics curriculum would teach students not just the mechanics of government, but also their rights and responsibilities as citizens. The curriculum would cover practical skills such as how to register to vote, participate in elections, lobby for issues and engage in civic representation. The assembly emphasized the need for an interdisciplinary approach, where civics education is integrated across subjects and evaluated using proficiency standards similar to those applied in English, math and science.

The New Hampshire Together citizens assembly’s work is far from over. Its delegates, along with a bipartisan group of legislators, are now tasked with turning these recommendations into actionable legislation for the 2024-25 session of the New Hampshire General Court. This next phase will be critical, as the success of this initiative will depend not only on the quality of the recommendations but also on the ability of lawmakers to enact meaningful change.

“We’re so very proud and humbled by the work our participants accomplished over the past year and especially over three intense days,” said New Hampshire Together Project Director Martha Madsen. “The people of New Hampshire selected the topics and found common ground on policies to address shared concerns. This was a heartening, hopeful experience.”

The topics discussed at the citizens assembly were familiar to New Hampshire Secretary of State David Scanlan, who spoke to the participants on June 23. Scanlan has already begun a broad-based voter education program for a range of Granite Staters, from school kids through veterans, seniors and minority groups, all to improve understanding of, and confidence in, New Hampshire’s voting process.

“Elections work best when they accommodate everybody,” Scanlan said. “As long as we can meet the needs of all the constituencies of an election, as equally as possible, we maintain confidence in that process.”

Keep Reading Show less

It’s time for “safe state” voters to be more than nervous spectators and symbolic participants in presidential elections.

The latest poll averages confirm that the 2024 presidential election will again hinge on seven swing states. Just as in 2020, expect more than 95 percent of major party candidate campaign spending and events to focus on these states. Volunteers will travel there, rather than engage with their neighbors in states that will easily go to Donald Trump or Kamala Harris. The decisions of a few thousand swing state voters will dwarf the importance of those of tens of millions of safe-state Americans.

But our swing-state myopia creates an opportunity. Deprived of the responsibility to influence which candidate will win, safe state voters can embrace the freedom to vote exactly the way they want, including for third-party and independent candidates.

Many voters worry about “wasting their vote” on candidates who can’t win. But safe-state voters are free to vote their conscience. In 2020, 36 states were won by at least 10 percentage points. Those states are a lock for Donald Trump or Kamala Harris even if millions of voters abandon them for minor parties.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. recently embraced America’s swing-state division. He suspended his independent candidacy only in the swing states to avoid being a spoiler. yet will offer voters a choice elsewhere. If you like Libertarian Chase Oliver, the Greens’ Jill Stein, or independent Cornel West and live in a safe state, give them your vote. Indeed, if they joined RFK in pulling out of swing states, they might earn even more votes because voters will know they’re not “spoilers.”

I certainly don’t suggest safe-state voters skip voting nor ignore down-ballot races — our votes are our voice wherever they’re cast. I’m not suggesting that either Harris or Trump aren’t the first choice of most Americans, nor that swing state voters can ignore the pragmatic reality that their states will decide the White House. But for voters who seek dramatic change, you have freedom in the safe states — and should use it.

Long-term, states can extend this voter freedom by adopting the ranked-choice voting system used by voters in Alaska and Maine and on the ballot in four states this November. With ranked-choice voting, you can support your favorite as your first choice. If that candidate doesn't have a chance to win and there's no majority winner, your ballot counts for your next choice among the strongest candidates in what amounts to an instant runoff. It ends “spoilers” and upholds majority rule.

Making us all swing-state voters demands an even bolder approach. It starts by recognizing its root cause. In 1960, 1976 and 1992, nearly two-thirds of states were battlegrounds — and they regularly shifted between elections. Now our system is far more rigid.

Our Constitution’s framers would be appalled at how our calcified partisan division marginalizes most Americans. Brought to life today, they would zero in on how state laws governing allocation of electoral votes make it politically useless to campaign where it isn’t close.

Those laws aren’t in the Constitution, and more states should join those that have passed the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact. With a few more adoptions — Maine being the latest to act this year — we can leverage the Electoral College to ensure that the White House always goes to the candidate with the most popular votes in all 50 states and Washington, D.C. Every vote would be equally meaningful in every election, and the candidates with the most votes would always win.

Looking to 2028, let’s help enough states enact the national popular vote plan to make all of us swing-state voters. Let’s help more states enact ranked-choice voting so we’re free to vote as we wish. But voters in safe states can matter this year: Just vote your heart.

Keep Reading Show less

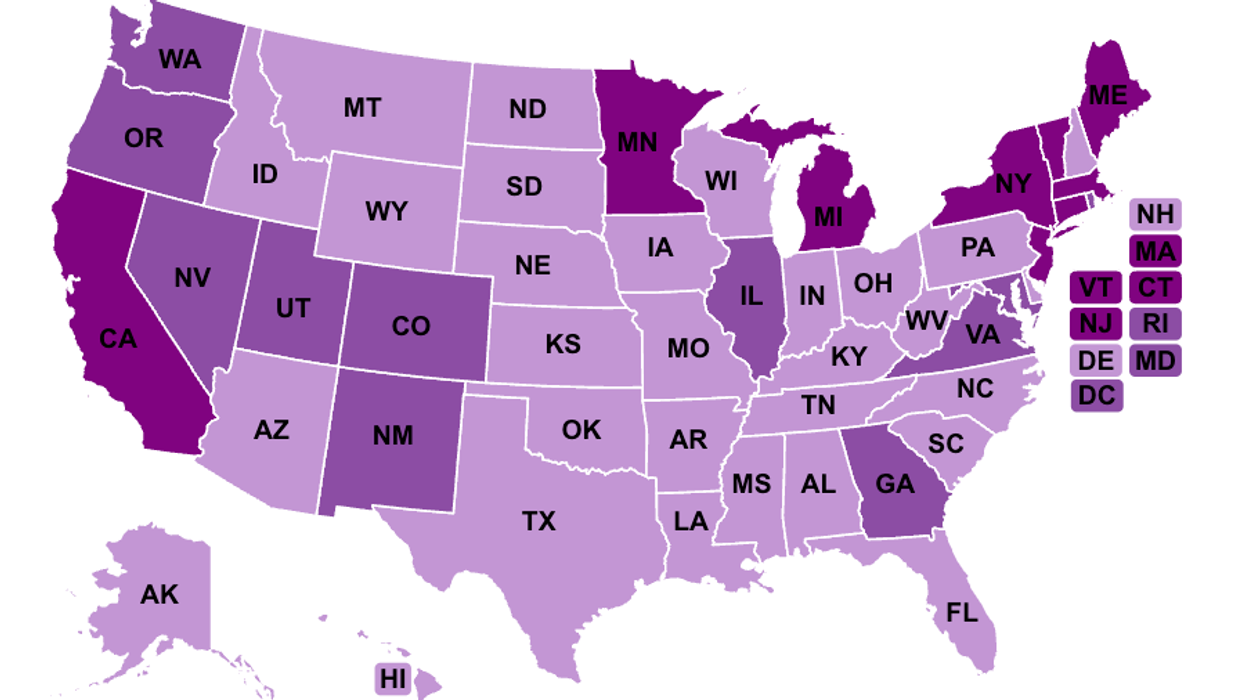

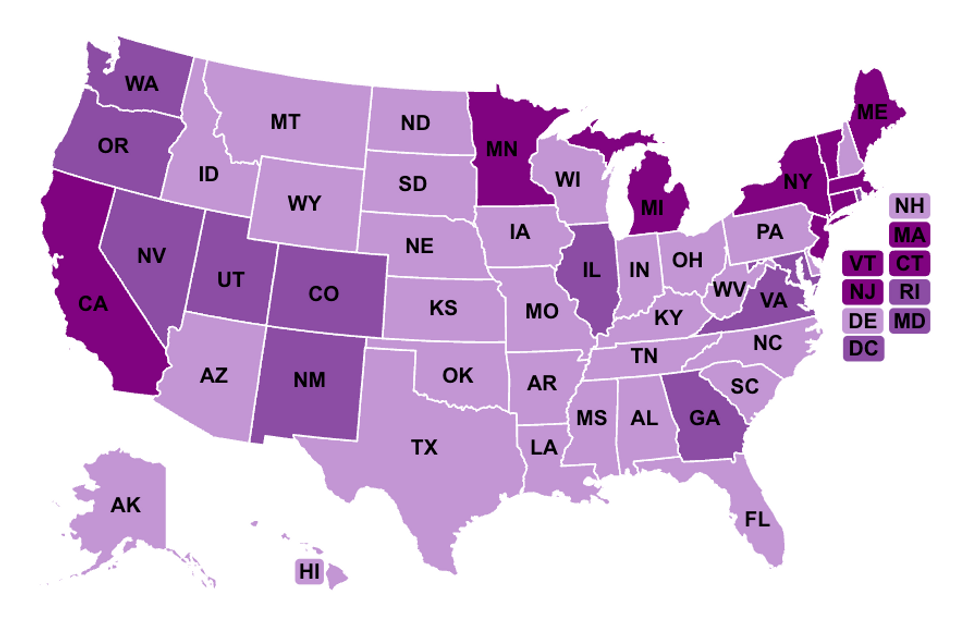

The National EduDemocracy Landscape Map provides a comprehensive overview of where states are approaching democracy reforms within education.

Dr. Mascareñaz is a leader in the Cornerstone Project, a co-founder of The Open System Institute and chair of the Colorado Community College System State Board.

One of my clearest, earliest memories of talking about politics with my grandfather, who helped the IRS build its earliest computer systems in the 1960s, was asking him how he was voting. He said, “Everyone wants to make it about up here,” he said as gestured high above his head before pointing to the ground. “But the truth is that it’s all down here.” This was Thomas Mascareñaz’s version of “all politics is local” and, to me, essential guidance for a life of community building.

As a leader in The Cornerstone Project and a co-founder of The Open System Institute I've spent lots of time thinking and working at the intersections of education and civic engagement. I've seen firsthand how the democratic process unfolds at all levels — national, statewide, municipal and, crucially, in our schools. It is from this vantage point that I can say, without a shadow of a doubt, that the democracy reform movement will not succeed unless it acts decisively in the field of education.

In Colorado, where I'm working on rural outreach in support of a ballot initiative that would create open primaries with final-four general elections, voters consistently ask how these reforms will impact their local communities. They care about the education their children receive, the way schools are governed and how decisions are made. They understand, perhaps more intuitively than most, that the local school board race is not just another election — it's the foundation of our democratic society.

The current democracy reform movement, while well-intentioned and ambitious, could be missing a significant opportunity by focusing primarily on high-profile congressional and statewide races. By potentially overlooking the 81,000 school board elections (plus many hundreds more higher education races) across the country, the movement is neglecting a critical arena. This oversight could ultimately undermine the broader goals of the movement, as the foundation of our democracy is built in the very schools governed by these too often overlooked races.

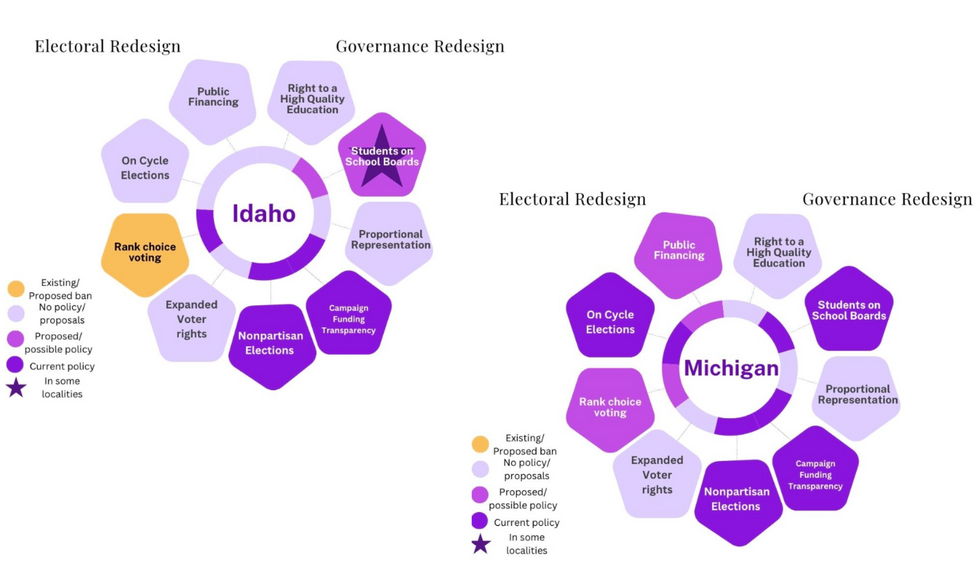

Therefore, we at Cornerstone are excited to announce the launch of the National EduDemocracy Landscape Map, a potentially first-of-its-kind research initiative designed to meet this critical moment for our democracy and education systems. The electoral and governance policies and practices we analyze as “EduRaces” and “EduDemocracy” are shorthand for the mechanics of school board races and higher education races that we believe have an opportunity to build democracy reform momentum.

This comprehensive resource brings together innovative democracy solutions and state-by-state analysis, offering a vital tool for leaders in both the education and democracy fields. This tool is essential at this moment in the democracy reform movement to take education seriously as a major lever for change — at the ground level.

Recent research highlighted in the Journal of Democracy raises critical concerns about the current state of democracy across the globe, particularly in light of the challenges posed by recent election cycles. These findings emphasize that while elections remain a key pillar of democratic governance, they are increasingly susceptible to manipulation, polarization and erosion of public trust. These issues are not just theoretical — they have real, tangible impacts on how democracies function and people perceive their governments.

Research into school board elections further underscores the urgency of addressing these democratic vulnerabilities within the education sector. Voter turnout in school board races is notoriously low in some parts of the United States, with only 3 percent to 4 percent of voters participating in Newark, N.J., and just a few hundred people voting in Oklahoma City, a city of over 700,000 people. This lack of participation allows a small, unrepresentative portion of the electorate to make decisions that impact the education of future generations. We know that moving from odd year to even year or aligned elections matter significantly - dramatically increasing turnout and producing board members more likely to represent the views of their communities.

Additionally, studies such as those by Kogan, Lavertu, and Peskowitz reveal a “demographic disconnect,” where voters in school board elections often do not reflect the diversity of the student population. For instance, in districts where the majority of students are racial and ethnic minorities, the majority of voters are often white, leading to governance that does not adequately address the needs of all students.

Moreover, the composition of school boards tends to be unrepresentative of the communities they serve, with most members being white men. In states like Arkansas, Missouri and Texas, over 60 percent of school board members are men, and 78 percent of all school board members identified as white. This lack of diversity can lead to governance that fails to consider the needs of all students, particularly those from minority backgrounds.

Compounding these issues is the trend toward increasing partisanship in school board elections. Traditionally nonpartisan, school board races in states like Florida, Arizona, and Kentucky are shifting toward partisan contests, which risks further polarizing these critical local elections. Students, the key user of our education system, are too sadly closed off and locked out from real and meaningful decision-making - not exactly practicing the democracy we preach.

This is all before we talk about the increasing use of school boards as tools for extremist politics and culture war issues, often exacerbated by low-turnout, at-large or plurality victories. As someone who has spent years working directly with superintendents and school boards I can say without a doubt these fractures prevent us from delivering on the promise of education.

The Cornerstone Project is an urgent call to action to address these issues — demanding that we take democracy innovation seriously within the education sector, as the future of our democratic society hinges on it.

I am an avid reader of Danielle Allen’s “democracy renovation” series in The Washington Post. I love her metaphor of renovating our democracy as one would renovate a house. If so, we may consider EduRaces the front door to the home. They are the door that most of our citizens see, use and open most often to access the power of our democracy locally.

There are some key reasons why education must be at the center of any serious effort to reform our democracy:

These reforms are not just about improving education governance — they are about strengthening democracy as a whole. By addressing low voter turnout, lack of diversity, and increasing partisanship in school board elections, we can create a model for broader democratic reform that can be applied at all levels of government.

By focusing on education, we can cultivate leaders, empower communities and ensure that democratic values are deeply rooted in the governance of our schools. The National EduDemocracy Landscape Map is a tool that the democracy and education movements cannot afford to ignore. It provides a comprehensive overview of where innovations are happening across the country and highlights where more work is needed.

The National EduDemocracy Landscape Map

The map highlights the significant differences in how states are approaching democracy reforms within education. For example, states like Michigan and Pennsylvania show substantial progress in both electoral and governance redesign, with existing or proposed policies for ranked-choice voting, public financing and expanded voter rights. These states are also advancing governance reforms like adding students to school boards and promoting campaign finance transparency.

On the other hand, states such as Idaho and Louisiana demonstrate more limited adoption of these reforms, with many policies either in the proposal stage or only implemented in select localities. This contrast underscores the varying levels of commitment and readiness across the country to embrace democratic innovations in education.

Advocates within and across states can leverage the map and our state EduDemocracy analysis to guide their efforts. For those in states with more advanced reforms, the map can help identify best practices and successful strategies that can be replicated or expanded. In states where reforms are less developed, the map offers a clear picture of the gaps and challenges that need to be addressed, allowing advocates to prioritize initiatives that have the potential to gain traction.

Furthermore, by facilitating cross-state collaboration, we hope the map will enable advocates to build coalitions, share resources and amplify their impact, ensuring that even in states with limited progress, there is a coordinated and informed effort to push democracy reforms forward within the education sector.

As many readers know, we are in an important inflection moment in our democracy. Working on our statewide measure in Colorado, I am reminded daily of the importance of local governance in shaping the future of our democracy. Just like my grandfather, voters want to know how these reforms will impact their lives, their communities and their children’s futures. To us, the answer is clear: If we want to build a more open, responsive and resilient democracy, we must start with education.

You may disagree with us about the impact and urgency to prioritize EduRaces in the democracy renovation space. Even if that’s the case, we would hope you would agree that these races are running with the flawed, closed models that are clearly hampering our ability to practice the full, open democracy that we all aspire to.

We urge the democracy field to get serious about EduRaces and for researchers, advocates and engaged citizens everywhere to dig into these important races. While of course banner statewide races are important, and municipal reforms matter significantly, education may be where we have the greatest opportunity to make a lasting difference — to build the front door to show all Americans democracy can work for them.

The Cornerstone Project is committed to leading this charge, and we invite everyone in the democracy movement to join us. Now is the time to harness the power of education to drive meaningful, structural change across our entire democracy.

The Cornerstone Project is a nonpartisan national education redesign and democracy renovation network aspiring to unrig the democratic infrastructure within education to reduce polarization, build a more just system, and unleash the potential for every learner to thrive by focusing on electoral redesign in Eduraces and governance reform.We bridge, learn, and act to support national, state and community leaders to transform Eduraces and education governance. The Cornerstone Project was founded by the Open Systems Institute, Seek Common Ground, and Education Civil Rights Now.