If you’ve ever asked your pastor or Sunday school teacher, “Who wrote the Bible?” you probably got one of two responses:

In a way, both of these answers are true, but by now you’re probably looking for a little more detail about the authors of the Bible. And rightly so: when you’re studying a book or passage of the Bible, it’s pretty important to know who wrote it.

But there’s a lot of nuance that goes into answering this question. The Bible didn’t fall out of heaven, and it was a long time in the making.

So, let’s take a closer look at the people whom tradition says wrote the Bible. Before we jump into the list of names, let me throw out a few disclaimers:

In case you’re just here for the list of names, here you go!

(I also made a poster with some fun facts about the authors of the Bible. It’s perfect for Sunday school classrooms and church offices.)

Heads up: this is a really long article. On to the nitty-gritty details …

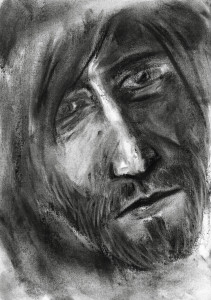

Moses is the prophet who leads Israel from slavery in Egypt to the edge of the promised land. He also wrote about 20% of your Bible. Of all the Old Testament prophets, nobody’s like Moses (Dt 34:10–12).

Moses is a Hebrew born in Egypt and raised in Pharaoh’s house. After killing an abusive Egyptian slave driver, Moses escapes the death penalty by running to the wilderness, where he marries and takes up life as a shepherd. Forty years go by, and God meets Moses in the wilderness (there’s a burning bush involved).

God commissions Moses: tell Pharaoh to let the Israelites go. Moses does so, Pharaoh resists, God judges Egypt with 10 plagues, and the Israelites leave. Moses takes the new nation to Mount Sinai, where the Lord brings Israel into a special relationship: from now on, Israel is God’s people, and God is Israel’s deity. Moses writes out the details of what that relationship looks like. These details are called the “Law,” and they take up most of the books attributed to Moses in the Bible.

The first book, Genesis, sets the stage for the other four books. It explains where the Jewish people came from, and how they ended up in Egypt. The next four books chronicle Israel’s physical and spiritual journey from Egypt to the promised land.

But Moses’ works aren’t over at Deuteronomy! He’s also the one who wrote Psalm 90.

Ezra is born long, long after Moses. But like the ancient prophet, Ezra leads a group of Israelites from exile in another nation back to the promised land.

Ezra is a scribe (someone who reads, writes, and interprets documents), and he’s especially well-versed in the Law of Moses (Ezra 7:6). He’s actually related to Moses: Ezra is a great-great-great(…)-grandson of Moses’ brother Aaron, which means he’s also got some priest blood in him (7:1–5). Ezra grows up in Babylon, but he is determined to move to become a missionary to his homeland (7:10), so he takes a group of Jews back to Jerusalem and begins teaching the people God’s ways.

Ezra is a key player in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah. He’s a religious leader in Jerusalem who calls the people around him to holiness.

The Jewish Talmud says Ezra wrote the book of 1 & 2 Chronicles (yes, they’re really two parts of the same book), and the book of Ezra. If this is the case, it makes Ezra the second-most prolific author of the Bible. Not bad for a guy you never hear about, right?

Nehemiah is a cupbearer to the king of Persia when he gets some disturbing news: his countrymen back in Jerusalem are in dire straits, and the city is in shambles (Neh 1:3). Nehemiah then gets the go-ahead from King Artaxerxes to rebuild the city walls and gates, and takes off for Jerusalem.

And get this: he gets the wall rebuilt in just 52 days (6:15).

Nehemiah’s more than a wallbuilder, though. Artaxerxes makes him the governor of Judah (Neh 5:14), and Nehemiah uses this position to point the people to God. He’s the one stationing soldiers, commissioning singers in the temple, and making sure the temple stays clean. Plus, he teams up with Ezra to rededicate the people to God (10:28–39) and hold them to their promises (13:4–31).

Nehemiah wrote the book that bears his name—and he wrote it in first person. Nehemiah has a very transparent writing style, often breaking from his story to record a prayer he made to God (4:4; 13:22).

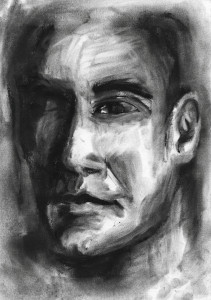

You’ve all heard of this guy. He’s the shepherd boy who killed Goliath the giant. He’s the war-hero king who delivered Israel from her enemies and established Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. He’s the jerk who killed off Uriah so he could have Uriah’s wife. And maybe most importantly, he’s a messiah: someone anointed by God to rule the people in wisdom and justice.

David is the focal character in the books of 1 & 2 Samuel and 1 & 2 Chronicles, and the books of Ruth and Kings tell us all about his family. David’s one of the Bible’s most important characters, but that doesn’t have all that much to do with David. He’s important because God makes a special promise to him: from David will come an everlasting kingdom with an everlasting king. Spoiler alert: that’s Jesus.

Somebody may have told you that David wrote the book of Psalms, but that’s not really the case. David only wrote about half of the Psalms—73 out of all 150, to be precise (though the Latin Vulgate and Septuagint credit a few more to him). Even so, that’s a lot more than any other psalmist.

These ones are his, specifically:

If you throw in the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Old Testament) and Latin Vulgate credits, it brings the count as high as 85.

Sidenote: another common myth about the book of Psalms is that it’s the longest book of the Bible. But that’s not really true, either.

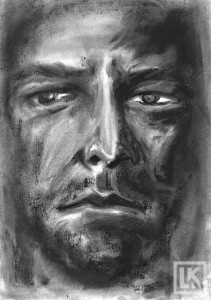

When Solomon succeeds his father David as king of all Israel, the Lord appears to him in a dream. He gives Solomon the ultimate “blank check”: Solomon names anything he wants, and God will give it to him. Instead of asking for cash or the heads of his enemies, Solomon just asks God for wisdom. And boy, does God deliver:

Now God gave Solomon wisdom and very great discernment and breadth of mind, like the sand that is on the seashore. Solomon’s wisdom surpassed the wisdom of all the sons of the east and all the wisdom of Egypt. For he was wiser than all men, than Ethan the Ezrahite, Heman, Calcol and Darda, the sons of Mahol; and his fame was known in all the surrounding nations. (1 Ki 4:29–31)

Solomon came up with 3,000 proverbs and 1,005 songs (1 Ki 4:32). Lucky for us, a lot of that wisdom is part of our Bibles.

Solomon is traditionally credited for authoring the books of Ecclesiastes and Song of Solomon. In the first, he asks, “What’s the point of even existing?” In the second, he celebrates love, marriage, and all kinds of sexual privileges that come with that.

Solomon contributes to two more books of the Bible as well. He’s the main writer in Proverbs, which is a book of principles for making decisions in wisdom and justice. Most of the first 29 chapters were written or curated by Solomon. The wise king also joins his dad in the book of Psalms: numbers 72 and 127 are Solomon’s.

When David commissions the temple in Jerusalem, he appoints Asaph and his family to lead worship (1 Ch 16:5). We don’t know much about Asaph, except that he’s a singer from the tribe of Levi (2 Ch 5:12). He and his family must have been some awesome songwriters, because 12 of the Psalms are credited to him (Ps 50; 73–83).

When Moses is leading Israel through the wilderness, a Levite named Korah challenges Moses’ leadership. That doesn’t end well—the earth swallows up Korah and his followers.

But Korah’s sons survive, and they have quite a legacy in the Bible through their music. The descendants of Korah wrote 11 psalms:

Before anyone gets overly excited, no, a Masters of the Universe character did not author part of the Bible (as far as I can tell). But the similarity in name is pretty funny.

Heman was a wise man who co-authored the eighty-eighth psalm with the sons of Korah. He was wise enough to compare to Solomon, but not wiser (1 Ki 4:31).

Oh, look, another psalmist! Like his relative Heman, Ethan was one of the wisest men in the world. You know, besides Solomon (1 Ki 4:31). He wrote Psalm 89.

We don’t know much about the author of Proverbs 30. He must have been wise enough for the Jews to include in their book of wisdom, but he doesn’t think to highly of his smarts compared to God’s:

Surely I am more stupid than any man,

And I do not have the understanding of a man.

Neither have I learned wisdom,

Nor do I have the knowledge of the Holy One. (Pr 30:2–3)

Again, the Bible tells us very little about this author. Lemuel was a king. possibly of a place called Massa (31:1). Some Bibles translate his intro to call him the “king of Massa,” but we’re not sure where that would be.

Here’s something cool about Lemuel: his contribution to the Bible is pretty much a tribute to his mom. She taught her son well, and now he’s passing on her wisdom to his readers.

Isaiah is the earliest,and arguably the most preeminent of the Major Prophets. His ministry spans the reign of four kings, and he seems to be responsible for some of the royal records (2 Ch 2622; 32:32). Isaiah marries a prophetess (Is 8:3) and has two sons.

In addition to proclaiming the word of God to the nation, Isaiah gives personal advise to the kings of Judah. He tells King Ahaz not to worry when the kingdom of Israel and Aram make war against Jerusalem (Is 7:3–4). He reassures King Hezekiah that the Lord will protect Judah from Assyrian armies (2 Ki 19:1–7; Is 37:1–7), but warns him that Jerusalem will one day be sacked by the Babylonians (Is 39:5–7).

And of course, the book of Isaiah is traditionally credited to him (though his disciples seem to have contributed to the body of work overtime). His prophecies cover the rise of Persian emperor Cyrus, the birth, death, and resurrection of Jesus, and the coming kingdom of God.

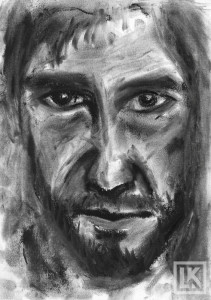

He’s the famous “weeping prophet” from the priests in the land of Benjamin (Jer 1:1). Jeremiah begins his prophetic ministry at a young age (Jer 1:6), and spends most of his time warning the nation of Judah that judgment is coming. He warns them about multiple Babylonian attacks, but the kings of Judah just won’t hear it. Jeremiah outlasts all the kings, though, and ends up offering counsel to the refugees of Jerusalem and the surrounding area. But even they don’t listen.

Jeremiah is like the Peter Parker of the Bible: the dude just can’t catch a break.

Books of the Bible Jeremiah wrote

Forget what you’ve been told about Psalms: Jeremiah is actually the longest book of the Bible. And that’s not all of Jeremiah’s writings. According to tradition, Jeremiah wrote the book of Lamentations, too. This book is a group of five acrostic poems that mourn the fall of Jerusalem. Jeremiah also wrote a few more dirges when the good king Josiah died in battle (2 Ch 35:25).

Ezekiel is one of the many Jews taken captive to Babylon (Ezek 1:1). He’s a priest from the tribe of Levi (1:3), but the Lord chooses him to do much more than make sacrifices. God sets up Ezekiel as the “watchman” for the Jews, because as bad as it is now, they’re about to get themselves into a lot more trouble.

Ezekiel makes a lot of sacrifices in his ministry. He eats cakes cooked over poop (4:12–15). He lies on his side for 430 days(4:4–6). His wife dies, but he doesn’t get a chance to mourn (24:15–24). He doesn’t have it easy.

But his prophecies are phenomenal. He sees the Lord enthroned above the cherubim (10:1–2). He sees the temple of God destroyed and rebuilt. He sees dry bones growing ligaments and flesh. He’s the watchman, and he watches some crazy things.

You’ve heard of this guy and his lion’s den episode. Daniel is a young nobleman from Judah who’s taken captive by King Nebuchadnezzar (Da 1:3, 6). Exiled to Babylon, Daniel quickly distinguishes himself from the other boys for his wisdom (1:20), and he’s one of the few characters in the Bible that reliably interprets other people’s dreams (2:28). He becomes a chief government officer in both the Babylonian and Persian empires (2:48; 5:29; 6:1–3).

And he also has some pretty intense visions. His prophecies tend to concern two major themes.

Daniel’s a wise man and he wrote an important book for those who want to study biblical prophecy.

Hosea’s claim to fame: God told him to enter a really unhealthy marriage.

Seriously, God has Hosea marry a prostitute and have a few kids (Hos 1:2). And Hosea does. When his wife takes up her old trade and starts sleeping with other men, God tells him to go bring her back home as his wife again.

Why? Because Israel has turned away from her relationship to God and chased idols instead. Israel is going to deal with the consequences of her actions, but the Lord plans to bring her back to him, just like Hosea brings back his wife (3:5).

All we know about this prophet is his father’s name: Pethuel. Joel writes a brief book of prophecy that explains two important phenomenon: the current plague of locusts and the coming day of the Lord.

Amos is a shepherd from Tekoa, a little town in the Southern Kingdom of Judah. The Lord gives him visions and calls him to journey north to prophesy against the king of Israel. As you can imagine, the false priests in Israel want to shut this Southerner down (Am 7:12–13).

Amos is an interesting character in that it seems he has no background in public ministry. When the false priest Amaziah tells Amos to go prophesy somewhere else, Amos responds: “I am not a prophet, nor am I the son of a prophet; for I am a herdsman and a grower of sycamore figs (Am 7:14).”

We don’t know much about this guy, except that he made a short prophecy against Edom. We don’t even get an “Obadiah, son of X” intro to his book, either, so we really don’t have much to go on.

But hey, if you love underdogs, you should check out his book. It’s the least-read book of the Bible!

One of the more famous characters in the Bible (albeit his is one of the least-read books). Jonah is a prophet to the Northern Kingdom of Israel (2 Ki 14:25), but the Lord sends him to Nineveh to warn the Assyrians of God’s coming judgment. Jonah sails in the other direction instead, gets thrown overboard, and spends three days in the belly of a big fish.

The fish spits him up, and Jonah is again called to preach in Nineveh. This time, Jonah obeys. But when the Ninevites repent, God spares them—and Jonah isn’t too pleased about that.

He is traditionally credited as the author of Jonah. If that’s the case, he must have had a moment of clarity after the events took place.

Micah is a prophet from Moreshetch in the Southern Kingdom of Judah, but he preaches to both the people in both the North and the South (Mic 1:1). We don’t know much more about Micah, but we do know that by the time of Jeremiah (around a century later), the elders in Judah considered him to be a true prophet.

In fact, the people quote Micah to save Jeremiah from the death sentence. When Jeremiah prophesies that Jerusalem and the temple will be sacked, the priests and false prophets try to get him killed (Jer 26:8, 11). But the officials and the people of the city remember Micah’s prophecies against Jerusalem, and stop the priests from murdering Jeremiah (26:17–19).

Nahum is a prophet, and calls himself an “Elkoshite” in his oracle against Nineveh (Na 1:1). We’re really not sure where Elkosh is, and so we don’t know much more about Nahum.

We don’t know much about this minor prophet, aside from his songwriting ability. The third chapter of his book is a prayer-psalm, one of the only shiggaion examples in the Bible ( Hab 3:1).

Zephaniah has some royal blood in him. He opens his tiny book of the Bible with his genealogy—which traces back to Hezekiah, the righteous king (Zep 1:1).

Haggai writes a very brief account of his ministry in the Bible. He encourages the Jews to finish rebuilding the temple of God, and his ministry is noteworthy enough for the scribe Ezra to give him a nod (Ezr 5:1–2). His recorded ministry spans about three months and 24 days (Hag 1:1; 2:10).

Haggai is the most specific of the Minor Prophets when it comes to dates: he gives the month and day of every message God sends him. Way to clock in your hours, Haggai!

Zechariah’s ministry gears up about halfway through Haggai’s (Zec 1:1), and he too encourages the people to get off their duffs and complete the temple (Ezr 5:1–2). Like Jeremiah, Zechariah begins delivering messages from God as a young man (Zec 2:4). He wrote down his visions and messages, giving us the book of Zechariah in the Bible.

In addition to being a prophet, Zechariah seems to be among the priests (Zec 7:2–5; Neh 12:16), which would mean he’s from the tribe of Levi.

Malachi is the last of the prophets to contribute to the Old Testament. He calls the post-exilic Jews to reconnect with the Lord, but apart from this, we don’t know much about him.

Matthew is one of the 12 apostles of Jesus, and one of the four evangelists who wrote down Jesus’s story. When we meet Matthew, he’s a tax collector for Rome. Tax collectors weren’t very popular in Israel, because they collected money from fellow Jews to pay a heathen king. But when Jesus calls Matthew to follow him, Matthew closes his booth down to serve the true King of the Jews. Then he brings Jesus over for dinner (Mt 9:9–10).

Matthew is called Levi in the other gospels, which may indicate that he’s from the tribe of Levi—we’re not sure (Mk 2:14–15; Lk 5:27–29).

Mark’s an interesting character in the background of the New Testament. We first meet Mark in the book of Acts. When Peter miraculously escapes from prison, he goes to Mark’s mother’s house (Ac 12:12). Later, Paul and Barnabas bring Mark along on their missionary journey as a helper, but he leaves them and goes back to Jerusalem (13:5, 13). When Paul and Barnabas prepare for their second journey, Barnabas suggests bringing John Mark again, but Paul won’t hear it (15:37–38). Paul and Barnabas disagree so sharply that they split up: Barnabas takes Mark to Cyprus, and Paul starts a new missionary team (15:39–40).

Mark matures, though. Decades later, Mark is considered useful to Paul (2 Ti 4:11) and a son to Peter (1 Pe 5:13). According to tradition, Mark is the one who writes down Peter’s stories of Jesus—which is how we got the Gospel of Mark.

Luke is a physician who accompanies Paul through thick and thin (Co 4:14; 2 Ti 4:11). His skills probably come in handy, because Paul takes a lot of beatings (2 Co 24ff).

But Luke’s greatest legacy is his contribution to the New Testament. Luke write more of the NT than anyone else (yes, even more than Paul). Luke’s a meticulous journalist who sets out to record the life and ministry of Jesus in consecutive order (Lk 1:1–4), and later records the history of the early church (Ac 1:1–2). He composes these accounts on behalf of a mysterious Christian named Theophilus, who wants to learn more about his Christian faith.

He’s another member of the 12 apostles, a former fisherman from Galilee who follows Jesus (Mk 1:19–20). The Lord gives John and his brother James the nickname “Sons of Thunder” (Mk 3:17). The Bible doesn’t say how he earned this nickname, but John does seem to have a stormy personality at times (Lk 9:51–56).

After the resurrection, John becomes a pillar of the early church (Ga 2:9). He writes a persuasive account of Jesus’ earthly ministry, death, and resurrection, and then writes four letters (the last one, Revelation, includes many apocalyptic visions). According to tradition, John becomes an elder at the church at Ephesus. He is eventually exiled to the Isle of Patmos (Rev 1:9).

Fun fact: of all the epistles in the New Testament, John writes the longest (Revelation) and the shortest (3 John). In fact, 3 John is the shortest book of the Bible.

Paul may not have the word count that Moses has, but he writes more individual documents than any other biblical author—13, to be exact.

When we first meet Paul, he’s not leading the church: he’s leading the charge against it. Paul (also called Saul) kidnaps Christians from the regions around Judea and brings them to Jerusalem to suffer the punishment for blasphemy. That punishment was often prison or death (Ac 8:3; 9:1–2).

But when Jesus stops Paul on the road to Damascus, Paul is forever changed. He becomes an apostle, the face of the church to the non-Jews around the Roman empire (Ep 3:1, 8). He travels across the world planting churches and spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ.

Paul’s letters to the Christians spread across the world make up his contribution to the Bible. Some of these letters were written to churches he had planted, others were to churches he hoped to visit someday. Paul also wrote to specific leaders in the local churches, like Timothy, Titus, and Philemon.

James the Just is the younger brother of Jesus (Mt 13:55; Mk 6:3), the son of Mary and Joseph. James doesn’t believe in Jesus while the Lord is going about his earthly ministry (Jn 7:5). But that all changes after Jesus rises from the dead. Jesus specifically appears to James (1 Co 15:7), and afterward James becomes one of the main leaders in the early church.

James is especially savvy when it comes to balancing freedom in Christ with respect for God’s holiness. When the church is undecided on how Gentiles should treat the Law of Moses, James settles the matter with a few pointers (Ac 15:13–21).

Later, James writes a letter to the Christian Jews scattered across the world, encouraging them to keep working out their faith. We call this letter the book of James.

You all know Peter. He’s the leader of the 12 apostles (Mt 10:2) and a pillar in the early church (Ga 2:9). Just as Paul is entrusted with bringing the gospel to the Gentiles, Peter is the face of the gospel to the Jews (Ga 2:7).

This guy is pretty hardcore. He walks on water (Mt 14:29), he cuts off some guy’s ear to protect Jesus (Mk 14:29, 31; Jn 18:10), and boldly declares that Jesus is the anointed one, the Christ (Mt 16:16). Yes, he’s also the one who denies Jesus three times at the Lord’s trial (Jn 18:15–16), but the resurrection totally transforms him. When the Holy Spirit comes to the church, Peter openly preaches the gospel of Jesus in the city.

Peter wrote two books of the Bible, and both are named after him. The first explains how Christians should live as aliens in this world: even though we’ll suffer, it’s nothing compared to the glory to come. The second letter urges Christians to remember what Peter has taught them even after he dies (2 Pe 1:13–14).

Jude is Jesus’ and James’ younger brother (Jude 1). Like James, he didn’t believe in Jesus during Jesus’ ministry on earth (Jn 7:5), but after the resurrection, he became a Christian. Jude writes one book of the Bible: a letter urging believers to “contend for the faith” (Jude 3–4).

A lot of people contributed to this massive collection of books. If you want to learn more about where the Bible came from and what it’s all about, check out my book, The Beginner’s Guide to the Bible. It’s a non-preachy, jargon-free journey through the world’s most important book.

We create research-based articles and handy infographics to help people understand the Bible.

Join our email list, and we’ll send you some of our best free resources—plus we’ll tell you whenever we make something new.